We start our 18th day on the trail with no inkling of the decision that lies ahead.

Leaving our plum camping spot, we find ourselves almost instantly on tough pathless terrain alongside Loch Stack. Progress is slow, so it feels as if we’ve hardly got anywhere when two hours is up and it’s time for our morning break. After that, we hit a lovely 4×4 track, which I’m just getting used to when Jeff announces we have to step off it and make our way across 1km of bog to the head of the next loch, Loch a Garbh-bhaid Mor. My boots fill with water within minutes. Even when we reach the loch, it doesn’t get easier; the path along its east bank is faint and rough.

After 2km we have to cross a river that flows in to the loch. It’s too fierce to cross where we are, so we have to trudge half a mile upstream to find a better place. Jeff makes it across holding Morris, using half-submerged rocks as stepping stones, but the bank on the other side is too steep for him to get up, so he has to come back. Meanwhile, I’m halfway across and have to make a tricky reverse manoeuvre! A bit further along, we manage to cross without mishap and walk back down to the loch to resume our slog along the shore, muttering to ourselves that ‘if the whole CWT was like this, we’d have given up and gone home’.

Fortunately, it isn’t. Gradually, the ground gets drier and firmer, the path more defined and the scenery gentler, with the river Rhiconich taking pride of place. I see a huge salmon leaping out of the water only minutes before a chap coming the other way asks ‘Have you seen any salmon leaping?’

It’s mid afternoon by the time we reach the remote hamlet of Rhiconich, and we’re more than ready for a drink at the hotel before looking for somewhere to pitch the tent. But the hotel door is locked and there’s no one in sight. Nor does it appear that there’s anywhere remotely suitable to camp. It’s all bit of a blow – the last few days have taken their toll and we’re craving beer, fish and chips and some friendly banter. What to do?

We decide to carry on a further four miles to Kinlochbervie, a fishing port with more amenities, and try our luck there. But along the way, a little cafe The Old Schoolhouse appears like a mirage at the roadside, offering cakes, teas and sandwiches. When I go inside to order (we sit outside because of Morris), I bump into our fellow CWTer, Daniel. He comes out to join us and we eagerly swap stories of our trail experiences since we last met.

We also learn from Daniel that two giant spanners have been thrown into the works of our progress to the end of the trail. The first is the tail end of Hurricane Lee, predicted to cause havoc across the north-west of Scotland over the next couple of days, bringing gale-force winds and torrential rain. And second, the military (who own much of the land around Cape Wrath) are starting ops on Monday (this being Saturday), rendering part of the territory we have to cross a no-go area. Daniel has decided to wait it out but we’re not keen to follow suit, and wonder whether we can use the remaining window of good weather to make it the whole way to the lighthouse. It’ll mean cramming two days’ walking in to one, so we’ll have to start early, but we’re up for it.

Jeff makes various phone calls to see whether our plan is feasible. He calls John Ure, the chap who lives at Cape Wrath and looks after visitors (a CWT legend) as well as the man who drives the bus from the ferry to the relative civilisation of Durness. It all seems doable – John says he’ll feed us when we get there and that we can stay overnight on the floor of the cafe and we’ll be able to get off the Cape the day after, either by ferry or on foot.

Suddenly, it feels as if our journey is rushing towards its conclusion. We bid Daniel farewell and continue on our way to Kinlochbervie, the evening sun casting a beautiful light on the lochs and mountains.

It’s dark when we reach Kinlochbervie, and we walk around for some time trying to find the heart of the village. (We later decide it doesn’t have one.) We find the hotel and go in to the bar, which is full of drunk and slightly hostile locals. The unfriendly bartender says we can’t get food because we’re not hotel residents. We have a desultory drink and a packet of crisps before heaving our packs out into the night to find somewhere to camp. The best we can do is a field just off the road that climbs out of the village. There are lots of cow pats – we just have to hope they aren’t recent ones.

Dehydrated meals have been invaluable on this trip – but tonight, I can barely stomach yet another dinner of chilli con carne with rice. We go straight to bed after eating – exhausted after a tough 15-mile day – and I sleep fitfully, dreaming of marauding cows and drunken locals searching us out.

The longest day

The alarm wakes us early. Not only do we have a long way to go – we’re also in a race against the weather. The rain is forecast to begin at 10am, with high winds to follow. I crawl out of the tent to an incredible sunrise.

We don’t bother with breakfast, planning to stop once we’ve got a few miles under our belt. The first section is all on road, winding up and down between treeless hills dotted with solitary houses. Then we get on to the track signposted to Sandwood Bay, one of north-west Scotland’s most famous beaches and something of an institution on the Cape Wrath Trail.

We don’t bother with breakfast, planning to stop once we’ve got a few miles under our belt. The first section is all on road, winding up and down between treeless hills dotted with solitary houses. Then we get on to the track signposted to Sandwood Bay, one of north-west Scotland’s most famous beaches and something of an institution on the Cape Wrath Trail.

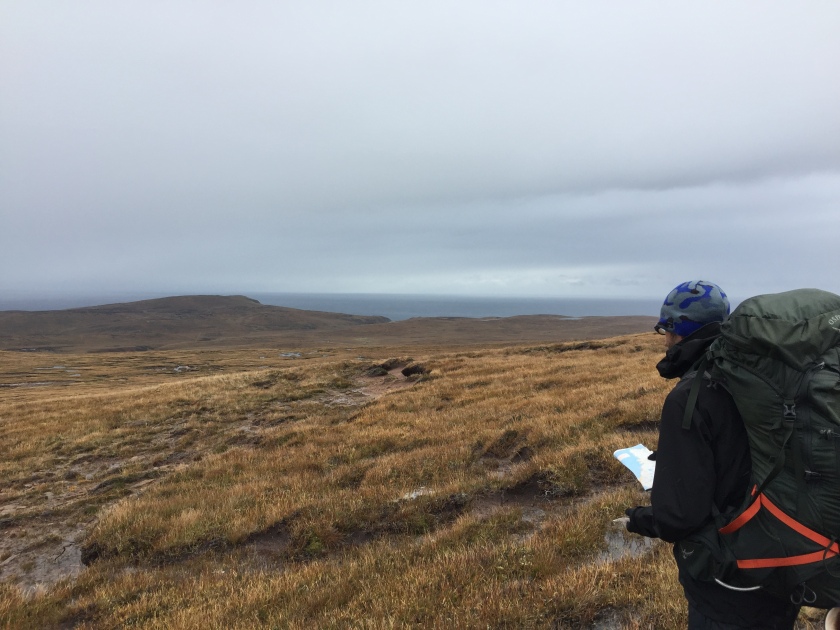

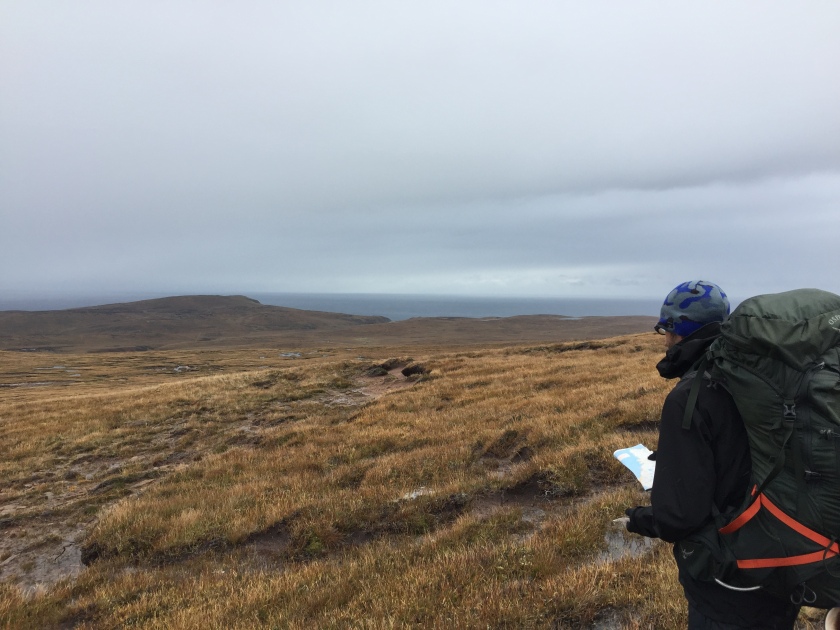

The track is wide and well made, if a little featureless, so we get a good few miles in the bag with ease. By 10am we are brewing tea at Sandwood Bay, sheltered by the dunes that back the beach. Just as we take our first sips, it begins to rain – right on cue – so we don’t linger for long. We have to make our way along the beach to pick up a path at the northern end; the pearly-white sand is strewn with amazing rocks and pebbles but we have to concentrate on leaping over the many fast-flowing rivulets (we don’t want to get our feet wet this early in the day, even though we know they’ll eventually be sodden). We climb up and away from the beach on a rocky path; at the top there’s nothing but a vast expanse of low-hilled green and rust bogland that we need to find our way across to the next ‘landmark’ – Strathchailleach bothy.

Jeff takes a bearing and we set off into the pouring rain. Herds of deer huddle in the mist, scarpering at our approach. When we reach the bothy, 90 minutes later, we go inside for some respite from the weather. I’m feeling a bit spaced-out and Jeff is worried that I won’t make it. I devour a tin of sardines and an oatcake while rain beats down on the metal roof; then we head out to continue across the same trackless and deceptively hilly terrain, that seems to go on for infinity. Every step is an effort and I feel as if I’m running on empty, being buffeted around like a rag doll.

Jeff takes a bearing and we set off into the pouring rain. Herds of deer huddle in the mist, scarpering at our approach. When we reach the bothy, 90 minutes later, we go inside for some respite from the weather. I’m feeling a bit spaced-out and Jeff is worried that I won’t make it. I devour a tin of sardines and an oatcake while rain beats down on the metal roof; then we head out to continue across the same trackless and deceptively hilly terrain, that seems to go on for infinity. Every step is an effort and I feel as if I’m running on empty, being buffeted around like a rag doll.

The barbed wire fence of the military zone comes into view. Red flags are flying even though the military operations are not meant to start until tomorrow. It’s disconcerting, but we climb over anyway and press on. I keep thinking I can hear helicopters, but it’s just the sound of water gurgling under the bog, mingled with the wind. After reaching the top of another hill, we finally see the road in the distance – it’s the only road on the entire Cape so we know it’s the one to the lighthouse. It’s still a way off but it’s heartening nonetheless.

I’m tottering and slipping and dragging myself up what seems to be an endless uphill gradient in the wind, rain and mud, wondering if we’ll ever get to that bloody road, when Jeff and Morris, 25m ahead of me, are suddenly standing on flat ground. It looks like a magic trick. But then I’m there too, and there is a mere 1.5km (uphill of course) along this pot-holed track between us and the lighthouse.

We don’t see the Cape Wrath lighthouse until we’re almost upon it. It’s partly the weather, but also a quirk of the way the land lies that it only comes into view at the last moment. There are steep drops on both sides of the final approach to the lighthouse lined by crumbling drystone walls – or nothing at all – and copious signs warn ‘UNSAFE’ (which doesn’t seem to deter the sheep from grazing dangerously close to the edge). The Cape is indeed a wild and desolate place, and arriving here in such extreme weather feels fitting.

The dilapidated buildings next to the lighthouse have an abandoned feel, and it’s difficult (fanciful even) to imagine that someone is going to be standing behind the counter of a cafe awaiting our arrival. At first this does appear to be the case; all the doors we try are locked and there doesn’t seem to be anyone around. Does John Ure really exist, or is it all a practical joke played on CWTers, we wonder? But then we push another door, and find ourselves inside the Ozone cafe. It’s deserted, but we ring the bell, as instructed by the sign, and wait.

Nothing happens. We stand there, shivering and dripping in our wet clothes. Our elation at reaching the Cape is gradually replaced by anxiety that we are the only ones here – we have no food left, limited water and there’s neither a phone signal nor electricity. We change in to dry clothing and are just considering crawling into our sleeping bags to get warm when we hear voices and dogs barking outside. It’s John, thank God!

He brings us a gas-operated heater and a clothes horse for us to hang up our sodden gear and invites us to come in to his house next door when we’re ready, for some hot soup and to warm ourselves by the fire. I feel like crying with gratitude.

When we turn up there, a few minutes later, he opens the door to the living room and we go in, assuming we’re alone. We are stunned to find it crowded with bizarrely-dressed and high-spirited men in a cloud of smoke. The source of their high spirits – beer and whisky – is spread out on the table and we’re poured drinks before the introductions are even done. This – it turns out – is the annual general meeting of the splendidly quirky Kearvaig Pipe Club, whose dress code for the year’s event is Crap Suits.

Slightly shell-shocked, after almost three weeks in splendid isolation, we join in with the banter as we thaw out, and before we know it, the evening light is fading and it’s time to retreat to our mattresses, which John has put down for us in the cafe. It’s only then that I realise Jeff has drunk more than his fair share of wee drams (not to mention smoking a pipe) and is, in fact, monumentally pissed.

I, however, am in no mood for nursing him. My guts are in turmoil and I’m having to run out with the cat shovel to duck behind the precarious drystone walls at regular intervals – I must have drunk some contaminated water earlier. My woes continue through the night, and we both wake up the next morning feeling terrible in our own ways.

The bad news is there’s no ferry, so the only way off the Cape is on foot. The good news is that John is giving his friends from the Pipe Club a ride to a place that will make the journey shorter (though it’s still 6-7 miles of walking). Fortunately, they are regulars here and know the way across the pathless bog that leads to the road to Durness, so we can tag along.

Jeff and I both force down a fried breakfast (we’ve not eaten a proper meal since that dehydrated chilli in Kinlochbervie) and pack our stuff. At around 11am, we crowd into the minibus and set off along the bumpy road. The views are stupendous, though my insides are still too miserable to allow me to appreciate it properly.

John stops the bus next to a steep, rocky slope that water is trickling down. It’s the path, apparently. We say our thanks and goodbyes and set off, quickly spreading out as we labour up the hill in a new deluge of rain and wind strong enough to blow us off our feet. At the top, a vast expanse of moorland unfolds, swathed in uneven tussocks, bog moss and heather. We slip and slide our way across it (me having to stop for emergency toilet breaks at frequent intervals).

John stops the bus next to a steep, rocky slope that water is trickling down. It’s the path, apparently. We say our thanks and goodbyes and set off, quickly spreading out as we labour up the hill in a new deluge of rain and wind strong enough to blow us off our feet. At the top, a vast expanse of moorland unfolds, swathed in uneven tussocks, bog moss and heather. We slip and slide our way across it (me having to stop for emergency toilet breaks at frequent intervals).

There’s a river to cross – sometimes it’s gentle enough to wade across but at the moment it’s a raging torrent and in a replay of yesterday’s rigmarole, we have to walk upstream for half a mile to find the bridge, and then all the way back down on the other side to continue towards Durness. I feel as weak as a kitten and thoroughly miserable.

At last, though, we start to see the odd car or lorry speeding along on the horizon – the road, the road! When we reach it, one of the Pipe Club members kindly squeezes us into his car and takes us the final few miles into the village of Durness. He drops us off outside the local shop and bids us farewell. Jeff enquires about accommodation in the area for the night while I buy Imodium, shampoo and new toothbrushes. Less than half an hour later, with the utmost gratitude and relief, we are opening the door to a warm, clean room with ensuite bathroom at the Wild Orchid guesthouse.

We’ve made it.

Epilogue

We walked the Cape Wrath Trail in September and October 2017. (John Ure reckons that fewer than 1000 people have completed it.) The blog had to come later, since we had no mobile phone reception or wifi access almost the whole way. The blog entries are based on the diary and notes I kept during the hike, and the photos are all taken on my iPhone. I’ve continued keeping a diary and taking photos for The Crazy Thing since we finished The Cape Wrath Trail – so stay tuned for the next stage of our Scottish adventures.

…and yet we’ve never quite made it a habit before. It’s hard to be heavyhearted when you reach the top of the dunes and look out across that vast expanse of sand, practically deserted at this time of year. Morris loves it.

…and yet we’ve never quite made it a habit before. It’s hard to be heavyhearted when you reach the top of the dunes and look out across that vast expanse of sand, practically deserted at this time of year. Morris loves it.

It’s colder now, too. But we’re travelling by van – not on foot – so we have the luxury of being able to carry more camping gear. When we pitch up I’m grateful for the foam roll mat under my Thermarest and the blanket on top of my sleeping bag – not to mention real milk from the cool box for our hot drinks!

It’s colder now, too. But we’re travelling by van – not on foot – so we have the luxury of being able to carry more camping gear. When we pitch up I’m grateful for the foam roll mat under my Thermarest and the blanket on top of my sleeping bag – not to mention real milk from the cool box for our hot drinks!

We don’t bother with breakfast, planning to stop once we’ve got a few miles under our belt. The first section is all on road, winding up and down between treeless hills dotted with solitary houses. Then we get on to the track signposted to Sandwood Bay, one of north-west Scotland’s most famous beaches and something of an institution on the Cape Wrath Trail.

We don’t bother with breakfast, planning to stop once we’ve got a few miles under our belt. The first section is all on road, winding up and down between treeless hills dotted with solitary houses. Then we get on to the track signposted to Sandwood Bay, one of north-west Scotland’s most famous beaches and something of an institution on the Cape Wrath Trail.

Jeff takes a bearing and we set off into the pouring rain. Herds of deer huddle in the mist, scarpering at our approach. When we reach the bothy, 90 minutes later, we go inside for some respite from the weather. I’m feeling a bit spaced-out and Jeff is worried that I won’t make it. I devour a tin of sardines and an oatcake while rain beats down on the metal roof; then we head out to continue across the same trackless and deceptively hilly terrain, that seems to go on for infinity. Every step is an effort and I feel as if I’m running on empty, being buffeted around like a rag doll.

Jeff takes a bearing and we set off into the pouring rain. Herds of deer huddle in the mist, scarpering at our approach. When we reach the bothy, 90 minutes later, we go inside for some respite from the weather. I’m feeling a bit spaced-out and Jeff is worried that I won’t make it. I devour a tin of sardines and an oatcake while rain beats down on the metal roof; then we head out to continue across the same trackless and deceptively hilly terrain, that seems to go on for infinity. Every step is an effort and I feel as if I’m running on empty, being buffeted around like a rag doll.

John stops the bus next to a steep, rocky slope that water is trickling down. It’s the path, apparently. We say our thanks and goodbyes and set off, quickly spreading out as we labour up the hill in a new deluge of rain and wind strong enough to blow us off our feet. At the top, a vast expanse of moorland unfolds, swathed in uneven tussocks, bog moss and heather. We slip and slide our way across it (me having to stop for emergency toilet breaks at frequent intervals).

John stops the bus next to a steep, rocky slope that water is trickling down. It’s the path, apparently. We say our thanks and goodbyes and set off, quickly spreading out as we labour up the hill in a new deluge of rain and wind strong enough to blow us off our feet. At the top, a vast expanse of moorland unfolds, swathed in uneven tussocks, bog moss and heather. We slip and slide our way across it (me having to stop for emergency toilet breaks at frequent intervals). It’s not just the being together that is novel, it’s the absence of anyone else. Some days, we walk in virtual silence for hours, lost in our own worlds; but it never feels awkward (unless one of us is sulking). Other days we talk incessantly or we play games, like Mr & Mrs, Who am I? or The A to Z of… fruit/sports brands/songwriters/positive adjectives (the options, as Jeff will attest, are endless).

It’s not just the being together that is novel, it’s the absence of anyone else. Some days, we walk in virtual silence for hours, lost in our own worlds; but it never feels awkward (unless one of us is sulking). Other days we talk incessantly or we play games, like Mr & Mrs, Who am I? or The A to Z of… fruit/sports brands/songwriters/positive adjectives (the options, as Jeff will attest, are endless).

When we reach Glencoul, two men – Barry and Dave – are doing some repairs and maintenance work on the bothy, but they are happy to make room for us and even get us to help with the planting of a rowan tree in the garden.

When we reach Glencoul, two men – Barry and Dave – are doing some repairs and maintenance work on the bothy, but they are happy to make room for us and even get us to help with the planting of a rowan tree in the garden.

There is a route choice to make here – our mutual fatigue leads us to opt for the easier route to Loch Stack via Achfary, rather than up and over Ben Dreavie. As a result, the remainder of the day sees us on 4 x4 tracks and quiet roads, with the dark, cleaved peak of Ben Arkle looming in the distance. North of the hamlet of Achfary, a tweed-clad estate worker (this whole area is part of the Grosvenor Estate, owned by the Duke of Westminster) stops us to ask where we’re heading, as there is a deer-stalking party going out the next day on the slopes of Ben Arkle. He also recommends a camping spot a mile or so further on, which turns out to be one of our best yet; a level grassy pitch with mountain views, a tumbling river and roaring stags. Bundled up in our sleeping bags, we look at the map and it’s quite a shock to see how close we’re getting to the final push to the lighthouse. It’s exciting, of course, but I also feel a reluctance for the hike to end because I’ve come to love the rhythm of our days on the trail. I’m not quite ready for this chapter of The Crazy Thing to end yet…

There is a route choice to make here – our mutual fatigue leads us to opt for the easier route to Loch Stack via Achfary, rather than up and over Ben Dreavie. As a result, the remainder of the day sees us on 4 x4 tracks and quiet roads, with the dark, cleaved peak of Ben Arkle looming in the distance. North of the hamlet of Achfary, a tweed-clad estate worker (this whole area is part of the Grosvenor Estate, owned by the Duke of Westminster) stops us to ask where we’re heading, as there is a deer-stalking party going out the next day on the slopes of Ben Arkle. He also recommends a camping spot a mile or so further on, which turns out to be one of our best yet; a level grassy pitch with mountain views, a tumbling river and roaring stags. Bundled up in our sleeping bags, we look at the map and it’s quite a shock to see how close we’re getting to the final push to the lighthouse. It’s exciting, of course, but I also feel a reluctance for the hike to end because I’ve come to love the rhythm of our days on the trail. I’m not quite ready for this chapter of The Crazy Thing to end yet…